Okay, that title is pushing it. And it should probably really be “The Good People at The Stockyards Lumber, Coal and Feed Co vs. The Customer From Hell.” But sometimes these HH Holmes lawsuit papers get a little dry.

Holmes, for those of you just joining us, is the 1890s multi-murderer who has become famous all over again since Erik Larson’s Devil in the White City retold the story of how Holmes built a “murder castle” full of secret passages and hidden rooms in which to kill visitors who came to Chicago for the 1893 World’s Fair.

One of our biggest and most popular tasks here at Chicago Unbelievable is sorting out fact from fiction when it comes to Holmes. It’s a real rabbit hole – for every expert, there’s an equal but opposite expert. For all the talk of Holmes killing fair visitors, there’s really one one fair visitor we can really blame him for killing. He was a swindler first and foremost, and seems to have mainly killed people he could make money from (he was always trying to get people to let him buy them some life insurance, though only one guy was ever dumb enough to fall for it), or people who knew too much about his swindling operations. Experts disagree as to whether he killed a dozen or so people or several hundred of them. One thing we can agree on, though, is that it was never wise to extend the man a line of credit.

|

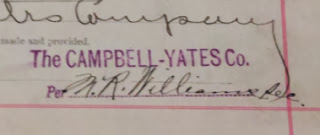

| Minnie’s signature, with a stamp for the Campbell Yates co, which owned the “castle.” Campbell was Holmes, Yates did not exist. Plummer, the lawyer, never figured this out. |

Lately I’ve been in and out of the archives, digging up lawsuits Holmes was in. The man got sued a lot, usually for buying goods and not paying for them. Yesterday I found a suit between him and H.W. Darrow, a man who somehow kept his name out of the papers, but was sued for supposedly-unlawful possession of one of the stores in the “murder castle,” as well as the room above it. The paperwork included the signature of Minnie Williams, who was Holmes’ secretary at the time (and probably his lover) (though she’s now one of his ten or so generally-agreed-upon victims, as well). It was a cool find, if only because the Feb 1893 date on the paperwork firmly established that Minnie was in Chicago before Spring of 1893, which is when some investigators thought she’d first arrived, which lends a bit more credence to her living in Lincoln Park in January, 1893.

The majority of Holmes lawsuits are just pages and pages of legalese saying “he took this money, said he’d pay it back, then didn’t pay it back.” Often, this stuff is in attorney Wharton Plummer’s handwriting – now there we have a guy we crappy penmanship. You can spend a long time staring at his writing, trying to figure out what he’s saying, and get a real headache before you finally decipher it and figure out that he wasn’t saying anything remotely interesting. He’s far more interesting in interviews; he never quite figured out that Holmes was a con artist, and claimed that the stories of the castle were “rot” (and, according to the papers, “he qualified the last word with an adjective in common use.”)

|

| This is Wharton Plummer’s very neatest writing. |

Now and then there’s some interesting info buried in the legalese of the lawsuit records, though; perhaps even a mystery, a story, or, at the very least, a new address to add to my “Where Was HH Holmes” map. You get just about all of those in the case of The Stock Yards Lumber, Coal, and Feed Company vs HH Holmes.

In March of 1893, less than two weeks before the Tobey Furniture company found that Holmes was hiding a bunch of their stuff in the hidden rooms of the “castle,” Holmes went to the lumber company (which was located near 47th and Halsted) and bought about 20,000 feet of lumber on credit – roughly 500 bucks worth – including a couple thousand feet of flooring, and a couple thousand feet of ceiling. The “Castle” being pretty well built by then, it’s anyone’s guess what he was using it all for. It was around this time that he started planning a building in Fort Worth, but he wouldn’t have used Chicago lumber for that. He may have planned to get it, not pay for it, and then sell it at a 100% profit, or he may have planned to burn it up for the insurance money. In any case, he never paid for it and managed to keep it from being repossessed, so the company sued.

Paperwork in the suit is dated as late as October, 1895, when Holmes was in prison. A news item from October, 1896, indicates that the case was still going on then, even though Holmes had been dead for nearly six months. When the case came back up, the company’s lawyer asked for the case to be dismissed, though he told the court, “I don’t know, personally, that the defendant is dead. All the information I have obtained was from the newspapers, which told us that he was hanged in Philadelphia.” The judge said “I think we can assume with safety that he is dead” and threw the case out.

|

A few months later, the Stock Yards Lumber Company was badly damaged by a fire, and doesn’t really appear much in any records or books much after that. Perhaps we can add them to the list of possible victims of the “Holmes Curse,” which we analyzed in a recent ebook at the left.

Some other suits I’ve dug through include a suit with Dr. MB Lawrence, who lived in the castle and loaned Holmes a few thousand bucks to convert it into a hotel (some documents from that are in our expanded Murder Castle ebook), one with Morrison and Plummer (wholesale drugs), The James Cycle Co (which is still in business), a bedding company, the Tobey Furniture Company, the Illinois Vault Co, a cigar company, and a handful of individuals who had the misfortune to loan the guy money.