New podcast! Get all our episodes here on the page or subscribe on iTunes!

According to legend, after Chicago’s first public hanging in 1840, the gallows were stolen by a man named George W. Green, who used the lumber for furniture that was then sold in his shop. Ironically, fifteen years later, the next public hanging was very nearly Green’s own. But after being convicted of murdering his wife with strychnine, he cheated the public out of getting to see hanging (still a popular spectacle in those days) by hanging himself in his prison cell with a makeshift rope. Not to be denied their morbid curiosity, the public was able to buy daguerrotypes of Green’s body, still hanging in his cell, at a “portable daguerrotype studio” at Randolph and Clark the next days.

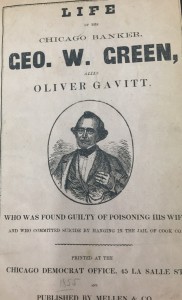

Besides the crass “selling postcards of the hanging” incident, the Green case is notable for two things: the first is that Green became the subject of a book entitled Life of the Chicago Banker Geo. W. Green, alias Oliver Gavitt, Who Was Found Guilty of Poisoning His Wife, and Who Committed Suicide By Hanging in the Jail of Cook County. The fifty-page volume was probably Chicago’s first true crime book.

The book – which is in the “special collections” at the Chicago History Museum and the University of Chicago Library – is quite a read. Basing their stories on interviews with neighbors and children of Green, the authors present him as a Dickensian villain who does everything but twirl his mustache as he tortures animals, beats his wife, poisons his neighbors, cheats his sons, kills his daughters, and steals the city’s first gallows (a story they admit is incredible, but insist is true and verifiable by several witnesses).

Even more notable, perhaps, is that the trial was way ahead of its time in its use of analytical chemistry. When Green

told neighbors his wife had died of cholera, he immediately had a grave dug in his garden for her. His brother-in-law suspected foul play, and Green was arrested. The body was exhumed, and various organs were placed in earthenware jars stopped with corks. Dr. James Blaney, an analytical chemist who would soon help found Rose Hill Cemtery, made detailed tests for traces of strcychnine, and detailed his methods and findings to the jury. His detailed testimony was reprinted entirely in the true crime book, as well as several medical and legal journals throughout the world. At various times, Chicago has, at various times, taken credit for being the first to use handwriting analysis (the Henry Jumperts “barrel” case in 1859), finger prints (Thomas Jennings, 1912), forensic use of bone fragments (Adolph Luetgert, 1897). By some measures we could add Blaney’s use of analytical chemistry to the list.

A couple of mysteries still endure for me: one is whether his wife was reburied right at the house, which stood near Twelfth and Loomis (Roosevelt and Loomis today). A drawing of the house makes it look like a prairie farmhouse. Private family plots on one’s property weren’t as common by then, but weren’t unknown. It’s quite possibly that her body was never moved.

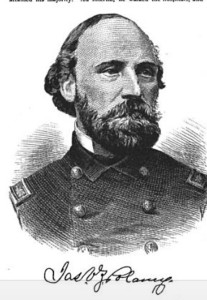

The other is whether any copies of the daguerrotypes of his body survive. As far as I know, none do, but a drawing of it was included in the book, and is reprinted below (if you’re the sort of person who reads history blogs you’ve probably seen far worse drawings, but consider yourself warned):

We’ve written Green into a new edition of Fatal Drop: True Tales of the Chicago Gallows!

Follow us on facebook, or twitter, or join the mailing list to stay up to date!

Podcast: Play in new window | Download